Good day, my fellow readers! I hope this leap day is treating you well. For me, it’s just another day, but I’ll persevere. Anyway, today I’d like to begin with a story. More specifically, it’s the story of me as a writer.

I mentioned back in the beginning of this series that I started writing my first book in the seventh grade, but I didn’t make it very far because I didn’t have a storyboard. Well, not long after I gave up, I thought up the storyline for a new novel, a fantasy which I initially called “A Knight’s Journey,” and later changed to simply “War.” I wrote this novel on-and-off for the next five or six years, completing a chapter or two, then taking a six month break, then writing furiously, then taking a year off, and on it went. I would write, then take a long sabbatical. When the anxiety, pressure and guilt finally got to me, I’d drag out my computer and write more, as much as I could before I lost interest and put it away for another long break. Then I hit my senior year and I decided that I just had to get that book done. So, almost exactly a week before graduation, I finally typed the last words of the epilogue and boom! My first novel, Torjen, was complete (minus the revising, which came later).

But in that time, over the course of those five or so years of writing one book, I’d compiled ideas, characters, plotlines and connections to over thirty-five other books that I decided to write in my life. There was only one problem: if I took as long to write each of them as I did to write Torjen, then I would die of old age before I made it even halfway down the list. That was when I committed to my book-in-a-year plan. Thereafter, once I began a book, I would plan everything in such a way that I would complete it in a year or less. As such, during my five years in college, I completed (year-by-year and in this order) Torjen II: The Search for Andross, Reality, The Hybrid, Torjen III: Diablo and finally the science fiction novel, Infrared. Most of these have yet to be published, but I promise they will be released from their digital prison cells someday. From college, I dove into my studies in seminary and, graduate studies being what they are, I was forced to suspend my novel-writing until I completed my studies. Finally, in the first year of marriage, I was able to dive back in with my newest creation, The Choice of Anonymity, only to take yet another year off afterward so I could make strides into the realm of publication. But regardless of whether or not I get published by this fall, I will definitely begin work on the sequel, tentatively called The Struggle With Conformity.

Now why am I telling you all of this? Because I believe one of the chief qualities of a writer can’t simply be good ideas, skills and talents. It can’t just be good planning, groundwork and carefully crafted worlds and characters. The quality which differentiates between the one-hit-wonder and the legitimate writer is productivity. A good career writer doesn’t write one novel and then live off of that for the rest of his life; if he does, he’s just a fluke, not a true writer. No, a writer writes, and he writes, and he writes because that’s what he does. He writes his stories because he must get them out, or because the need to write, to share his thoughts is driving him mad. Or perhaps he’s in a deep (non-romantic) love affair with the craft itself. He doesn’t just think about writing; he writes!

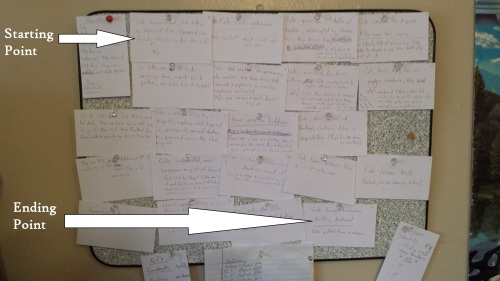

But too often, I myself have struggled with long periods of inactivity. After all, it took me five years to write my first book! So what’s the solution? For me, what makes the one-year rule successful is a concept that probably brings a nauseating sensation to many stomachs and a woozy disgust to many minds: deadlines. Yes, that terrible beast which plagued each of us in school is what I have to enforce upon myself: deadlines. Check out the 2014-2015 schedule I crafted for The Choice of Anonymity below.

After completing my storyboard of the plot, I looked at how much was to compose each chapter and I gave myself the necessary time to complete it. Notice, for instance, that chapters ten, twelve and fourteen each took nearly a month to complete, while most of the others took about two weeks. That’s because those chapters were whoppers. On the other end of the spectrum, the prologue and epilogue each took about a week because those were miniscule. And chapter nine took another month because, in all honesty, I took two weeks off for the holidays. It wasn’t my most megalithic chapter.

By sticking to these deadlines, I made the writing of my book into a much less daunting task, and I ensured that less than a year after selecting the first few words of the story, I was writing the last few lines. This is the tactic that works for me, the strategy which keeps me productive and ensures that I will not die of old age before I make it halfway through my list of future books (which still rests at around thirty-five to forty, although I now have other follow-up ideas if my memory isn’t shot by then).

If the system of deadlines doesn’t work for you, then I encourage you to find something that will. But remember, you absolutely must find something that works. If you don’t, your productivity will be very low – if alive at all – and a writer you will cease to be. Stay the course, my friends. Be committed to seeing your works through.

Until next time, friends…

Stay tuned for next week’s finale to our eight-part series on the craft of writing, in which I’ll discuss the nature of beauty versus exploitation in storytelling!