Greetings, and a fair day to those of you reading this! I hope the past week has treated you well. Mine has been busy getting back into the swing of things, but I’ll soon pick up the energy I need. Now I would like to begin a new seven-part series on the craft of writing. Essentially, I want to cover everything from plot to character development to pacing, and the most important things in between. Most of what I plan on sharing with you is what I’ve picked up over the course of my…twelve?…years of writing. I’m not claiming to be an expert, but based on what I’ve learned over the years, I’ve found that I’ve become more sensitive to examples of poor writing. In addition, my writing skills often translate into a deeper understanding of stories in any medium, which is why when I watch movies with my wife, I’ve learned to keep my predictions to myself; I have spoiled too much with my startling accuracy, to my wife’s utter annoyance.

In my senior year of high school, my English teacher taught us that there are three chief components to storytelling: plot, characters and setting. A perfect balance of these will create a balanced story, but you can still be memorable if at least one of these is done well. Today, I want to talk about what I feel to be the most important of these three: plot. After all, without a plot, there is no story. If you focus on just character development, you end up with a psychological profile but no story, and if you focus on just setting, you’ve essentially described a painting. Plot, my friends, is the action of the story, that which pushes the reader forward in time (or backward, if the plot involves time travel).

So then what is plot? Plot is the events of the story. This is what happens. Suppose, for instance, that I were to tell you a story where a man and a woman go into the woods, only to confront a werewolf, who chases them back to the village, then that confrontation and the ensuing chase would be the plot.

Since this is the basis of the story (what makes a story a story), then this is where I would advise you to begin. This is born from a single, core idea, perhaps an event or a scenario. Perhaps a virus infects a family member and is determined to be highly contagious. Or perhaps a man goes to visit his dear aunt, only to find a colony of ants spelling out words in her living room. I began watching a movie earlier called Don’t Blink, in which ten friends go up to a cabin for the weekend only to find all people and wildlife have seemingly vanished from the area (kind of similar to Ghost Ship, only at a cabin instead of a lost vessel). It doesn’t really matter what that event or scenario is, but once you have it, then you can begin to play around with it. What will a set of characters do in response? Will they search for answers? Will they go on a quest? Or will they turn on each other?

From this, you begin to develop the plot, threshing it out into a story. Here’s where it begins to get difficult, and to demonstrate this, I’ll first explain a tactic I used unsuccessfully when I was young, and then I’ll describe my regular process now. When I was in the seventh grade, I began to write a book called The Choice of Anonymity. The plot was simple: a shapeshifter begins murdering people in a town, and a kid has to stop him. That was literally all I had when I first began writing. So naturally, I didn’t get very far. After about two or three chapters, I realized that I had no idea where I was going. I had no endgame in mind and no guide to get me there. So the book ended.

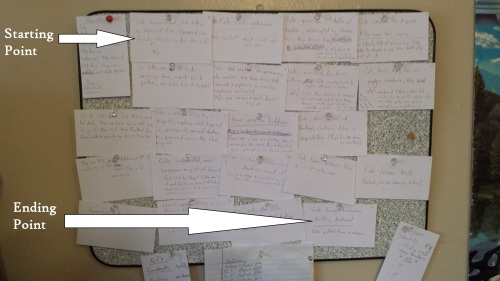

Fast forward eleven years. I chose to return to The Choice of Anonymity, but I wanted to do it right this time. So before I even began, I thought out a bunch of scenarios all relating to that one central theme (the murderous shapeshifter). I thought of a group of zombified students chasing my characters through a school. I thought of a daring escape from a collapsing hospital. I imagined a religious experience at the altar in a church. A murder in an observatory. A house that comes alive. I wrote each of these on a notecard. I chose a starting point (my main character sees a neighbor’s house burning down), and an ending point (my main character has a confrontation with the shapeshifter himself), and I put those on either end of a spectrum. Then, all I had to do was organize the rest of the events in a logical order, fill in the blanks to connect them into a reasonable storyline, and then bam! I have my plot. This is called storyboarding. Below is a picture of my storyboard for The Choice of Anonymity.

By storyboarding, you’re able to do a number of extremely important things. First, you’re able to add much more complexity to the storyline. After all, if you don’t fully understand your story, then you’re fairly limited, for you’ll be forced to either keep it simple or any complexity you try to add will become incomprehensible. How many times have you watched a television show only for it to become painfully obvious that the writers have no idea where they’re taking it? Heroes, for instance, knew exactly where it was going in the first season, but after that, the writers fumbled around with no storyboard, and the quality was significantly diminished. The same happened to Supernatural once it went beyond season five. It’s still enjoyable, but just nowhere near what it once was. On the other end of the spectrum was Carnivale, which had a storyboard for more seasons than the show got picked up on (if only it could have controlled its budget, alas). So the storyboard allows you to have a much greater control over your story, giving you the power to develop greater – but, more importantly, coherent – complexity in it.

But there’s also a much more fundamental purpose to the storyboard which I’ve already hinted at: coherency. I’m talking about plot holes. A plot hole is a place where you look at the story and realize that something didn’t quite work out logically. Perhaps a character reveals information that there’s no way he should have known. Or perhaps your antagonist tracks your characters to a tavern, only for you to realize there’s no way he should have known they were there. These issues can be catastrophic for your story, for if they are critical enough to the plot, then the whole plot can break down, leaving your story in unappreciated shambles. But the storyboard allows you to correct for this! By looking at the storyboard closely for hours at a time until your eyeballs begin to ache, you can pinpoint plot holes and then, with the whole storyline sitting before you, you can reconfigure and massage the plot until the problem is reconciled.

Finally, when your storyboard is perfected, polished and totally coherent, you can begin the next few steps. But before that, I want to touch on one last concept: organic writing. Organic writing is when you sit down with no plan and choose to go wherever the story takes you. This is in stark contrast to what I’ve described in this article. I will say that organic writing is a good and powerful tool for improving your own abilities as a writer. I, myself, do it once every couple of weeks or so in order to test myself and keep my writing mind sharp. However, organic writing is, in my opinion, better suited to shorter works, like short stories or flash fiction (stories of a thousand words or less). But if a book is what you’re going for, I don’t believe organic writing will get you there, at least not without a severe sacrifice in quality. It sure didn’t work when I first attempted The Choice of Anonymity.

I hope this has helped you writers out there. If your process is different than mine, please, I encourage you to share it in a comment. After all, a challenge to do things differently is a great opportunity for growth.

Until next time, friends…

Stay tuned for my next blog post, in which I’ll discuss character development!

Pingback: The Craft of Writing, Part Five: Information | The Outside View

“Lost” was another show that clearly lacked a plot. From the beginning, they just had random things happen with no plan of what they were, why they happened, or anything. They started to tie things together, but they’d kill off a character before fully explaining his/her involvement and they’d add detail to something weird then contradict themselves, and then suddenly, the series was over.

I think Ghost Ship had a ton of potential to bring everything together, but they added one or two scenes that didn’t make sense when everything else could have, and so the movie went from really cool to “badly written” (in my opinion).

I have to agree with you for the most part. Liz and I are halfway through the last season, and while I have enjoyed the ride, there are a few things that still plague my brain (like Libby’s backstory?! Hurley’s girlfriend who was in the psych hospital with him?!). And as far as Ghost Ship is concerned, it had excellent potential, but I think they rushed through the explanatory backstory too much for it to have any realistic impact, far too quickly to entirely make sense out of. I think a prequel to that would be fantastic, though.

Pingback: The Craft of Writing, Part Seven – Productivity | The Outside View