Good day and salutations, my dear readers! I appreciate your taking the time today to listen to my thoughts…or read them, I suppose is more appropriate to say. Before I get started on today’s topic, I need to make two announcements. First, next month my wife and I are moving cross-country to resettle in our home state of Indiana. She received an excellent job offer there and it’s right where our family is, so the move is ideal for our future. Unfortunately, I do not currently have any job offers there, which means that I may be unemployed upon our move. So with this in mind, I’m asking that you spare some prayers for me as I engage in the job search. Ideally, I’d like to make money as a writer, but that’s excruciatingly slow going right now, so a job is needed, and for that, prayers are priceless.

Secondly, all of this moving, being right around the time of our regular vacation, means that for the next month or so my blog posts will be somewhat sparse. After this, my next post will likely be on June 27th, three weeks from now. But there’s news on that front! With my newfound interest in Wattpad, an online fictional writing website, I’ve decided that once I settle into my regular routine in July, I’ll only be posting blog posts biweekly, rather than weekly. In the intermittent weeks, I’ll begin posting a new, ongoing steampunk series called The Rift. My plans for this series cover everything from flying, steam-powered dirigibles to Lovecraftian monsters, so this is bound to be a lot of fun, and I’m really looking forward to it!

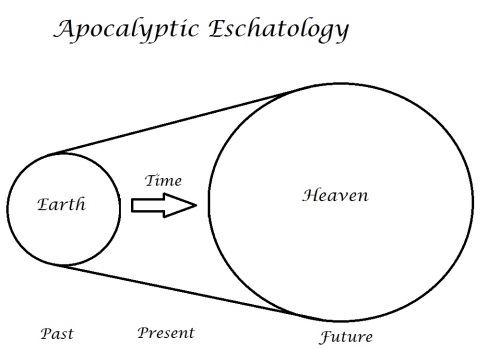

Now, onto the topic of today: the book of Enoch. I’m sure many of you have heard of this strange piece of literature, but if you haven’t, let me tell you about it. The book of Enoch (which I’ll simply call Enoch from this time on) was written sometime in the late 300s to early 200s BC, shortly after the time of Alexander the Great. It’s what’s known as an “apocalyptic text,” meaning that it reveals hidden aspects of history, predicts the future and foresees the ultimate end of the world (an event which scholars call the “eschaton,” hence the name of this literary style: apocalyptic eschatology). In the canon of the Bible, we have only two thoroughly apocalyptic texts: Daniel, which is half-apocalyptic, and Revelation. Enoch is essentially the perfect example of an apocalyptic text, as it matches up with nearly every aspect which defines a book as apocalyptic, even moreso than Daniel and Revelation. Enoch gets its name from its claim to have been written by the Biblical character of Enoch, a man who, according to Genesis 5, was so close to God that he was taken up to Heaven and was seen no more. It’s also notable that he was the great-grandfather of Noah. Yes, that Noah. The one with the boat. Now this is, of course, completely untrue seeing as how we know that Enoch was written shortly after the time of Alexander the Great, nowhere near the ancient days when the real Enoch likely lived, but apocalyptic texts are known for claiming to be written by famous people (like Ezra, Moses, Noah and even Adam in one case).

Those are the basics of Enoch. But what especially fascinates me is what we find inside it, mainly in the first section, known as “The Book of the Watchers.” In this, we find not one, but two separate rebellions by angels in Heaven. Each of these rebellions are orchestrated by a class of angels known as “Watchers,” sometimes translated as “Grigori.” Let’s explore these two rebellions in detail.

The First Rebellion: For the Love of a Woman

The first rebellion was instigated by an angel named Shemyaza (sometimes translated as Shimyaza, although with the lack of vowels in ancient Hebrew, it was likely something similar to Shmyzh, so feel free to spell it however seems best to you). Shemyaza was a prominent angel among the Watchers, and their job was, as you can probably guess, to watch over the earth and mankind. Unfortunately, this went badly for Shemyaza as he fell in love with a human woman. A large number of the Watchers, following his example, also fell to Earth and began breeding with human women. Naturally, kids entered the picture, but you wouldn’t expect half-angel/half-human hybrids to be normal, would you? Of course not. So into the scene enters the Nephilim, sometimes called Rephaim, great and powerful giants. Now this is especially important as this is a play off of a passage in Genesis 6 (of our actual Bibles) which describes the “sons of God mating with human women…creating the Nephilim, giants mentioned in legends of old.” Until the time when Enoch was written, the Nephilim were speculated on, and some minor legends circulated, but Enoch was by far the most sophisticated adaptation of their mythos.

Unfortunately, these Nephilim proved to be far less than altruistic. Enoch describes how they conquered, oppressed, killed and (as is sometimes claimed) even ate humans. Naturally, this did not bode well for God’s beloved humans, so he took action on two fronts. First, he sent the global flood not to wipe out a wicked humanity, but to destroy the mighty and wicked Nephilim, who all drowned. However, as misfortune would have it, though their bodies were destroyed, the spirits of the Nephilim survived, thus forming an origin story for demons. Secondly, God took Shemyaza and his followers and he chained them up beneath the earth, to wait as prisoners until Judgment Day. And thus was the first rebellion ended.

The Second Rebellion: Arts and Crafts

There was also another Watcher known as Azazel. While Shemyaza’s name seems to be an invention of Enoch‘s writer, Azazel actually does appear in the sixteenth chapter of Leviticus (again, of our actual Bibles), where he is a mysterious character to whom the Israelites are to send a scapegoat from time to time. For clarification, it must be said that the mention of Azazel in Leviticus predates the Israelite concept of demons, which entered their mythology much later on. Anyway, Azazel is another prominent member of the Watchers. Now while he didn’t end up falling in love with a human woman, he did find the inclination to start sharing knowledge with humanity. He taught them medicine, metalwork, jewelry-making and, more dangerously, sorcery and magic. All of these things were, according to Enoch, forbidden by God, so Azazel and his followers were, like Shemyaza before them, chained up beneath the earth to await Judgment Day. Unfortunately, humanity had learned far too much at this point and the corruption by Azazel had left a lasting imprint.

Analysis

There are many fascinating things to discuss about these two rebellions. First, I wouldn’t be honest with you if I didn’t remind you about a key verse in the book of Jude (again, in our actual Bibles). Only six verses into the book, we find a curious mention of how “the angels who did not keep their proper domain, but left their own abode, [God] has reserved in everlasting chains under darkness for the judgment of the great day.” That is, almost exactly, a verbatim quote from the relevant passage in Enoch, which predates Jude by almost half a millennium. Thus, Jude had to have read Enoch, or at least been familiar with the story. But the curious thing is how he references this passage as if it’s scripture. That raises some very interesting theological questions, but I’ll leave that up to you for now.

More importantly is the social analysis of these two rebellions, which is tied in with the origin of belief in fallen angels. Enoch was written at a time of enforced Hellenism. Essentially, the ruling Greeks were trying to force their culture, philosophy and mythology upon the Jews. Some Jews were more accepting of this, while others became nearly militant in their rejection of all things Greek. We can actually see this reflected in the stories. First, we have Shemyaza, who leads the Watchers in interbreeding with human women and producing dangerous monsters. Many Jews saw this as a metaphor for how the Greeks were intermarrying with Jews and creating half-Greek/half-Jewish children, thus diluting the ritual purity which the Jews had striven for in maintaining their religion. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with interracial/intercultural marriage, but I’m saying that the Jews at that time did think there was something wrong with it. So to the Jews who were reading the newly written Enoch, they found a metaphor for what was actually happening around them.

The second rebellion is nearly identical, except rather than intermarriage being the issue, the problem was the spread and influence of Greek medicinal, artistic and philosophical ideas. I’m sure many of the Greeks saw themselves in the role of Prometheus, “sharing the fire of knowledge with those backcountry Jews!” But the Jews would have seen Prometheus as an archetype of Azazel, that angel who was punished for teaching things man was not meant to know. Both rebellions, therefore, stand as symbols for the corruption of pure Judaism with Gentile culture and influence. And just as God had punished the angels, so they believed – according to most apocalyptic texts – that God was going to punish the Gentiles as well, for the same crime of diluting the proper relationship between God and his chosen people. This is definitely something worth thinking about in our own day and age.

Until next time, friends…